|

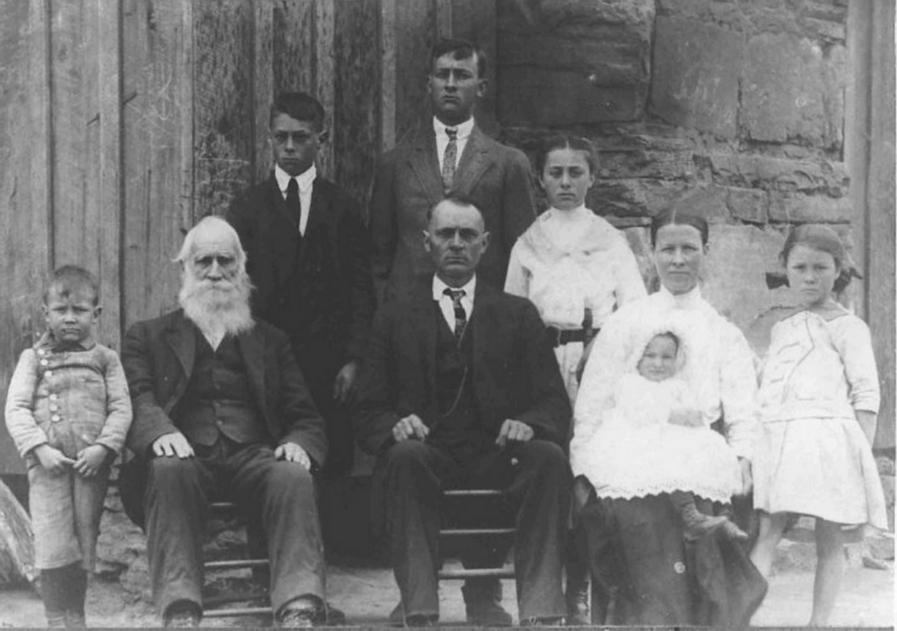

Imagine leaving our complicated modern

lives to travel up an old, nearly impassable,

mountain dirt road to visit with an aging

hunter and farmer and his family with the

singular mission to hear and record their

stories for future generations. In 1939 A. T.

Long did just that when he visited Marson

Baynard's home as part of the Federal Writers

Project American Life Histories. The life of

Marson Baynard became one of thousands of

stories in this Work Projects Administration

(WPA) effort to employ writers and other

artisans hard pressed by the hard times of the

Great Depression and difficult economic

recovery. Beyond helping launch the careers of

many significant literary figures, these WPA

interviews have become a valuable resource for

historians and other researchers. This project

has also become a classic example of the

problems associated with documenting and using

oral history sources.

The essential difficulty with oral history

comes from the reality that living spoken

conversations, no matter how treasured, simply

do not create a fixed document that can be

neatly archived. People and their memories die.

When words stop reverberating in the ear, the

experience of them is gone forever leaving only

echoes of memory. While memories last longer

than words, they also fade with health and

perspective and time. And everyone has

experienced conversations where the following

day the realization of what should have been

said rises clearly and brightly as the emerging

morning sun. Ultimately, the use of oral

history as a source, just as any source,

requires careful consideration of its

reliability by the researcher. However, oral

history is unique in that researchers are also

frequently the interviewers who convert the

living memories to a document that can be

archived. This role presents additional

challenges and responsibilities.

The first special consideration in

documenting and recording oral history is the

technology that makes it possible. Oral history

from the eighteenth century is simply not

available due to technology limitations.

Throughout the twentieth century, interviewers

and archivists struggled with recording

technology. It remains a significant factor in

discussions among professional oral historians.

In the case of the WPA interviews, the

technological problems resemble the long string

of events leading to the nearly complete loss

of the 1890 Federal Census. Often, memory and

notes alone served as the recording media.

Other times, interviewers used the bulky yet

somewhat portable media of wax cylinders to

save these conversations for posterity. For far

too long, instead of reformatting the

recordings onto new technology, they were

stored in an overly warm environment. Heat and

wax do not mix well, and the resulting loss is

forever. Other technology has come and gone or

largely faded away. Metal and vinyl albums.

Eight track and reel to reel tapes. In one case

significant to Western North Carolina, writer

John Parris used wire recordings. These

recordings are archived in hopes that

eventually a working machine can be located to

play the recordings and transfer them to more

modern media. In the meantime, questions remain

as to whether or not the information recorded

on the wires still exists at all or can be

retrieved. Currently an increasing movement

promotes the use of digital formats for

preserving recorded interviews with the hope

that using Internet friendly file formats such

as .wav will allow continued access. However,

the challenge to provide for necessary

reformatting remains as the computer industry

creates new technology faster than current

technology can be integrated into existing oral

history projects. Beyond these issues, even the

latest recording device cannot help when

batteries go dead or the interviewer runs out

of tape or disks or forgets to hit the record

button. Practicing with even the most basic

equipment and having back-up supplies is

perhaps the most overlooked but vital part of

the interview process.

The only way to guarantee the interview will

survive technology changes remains the long

hours necessary to transcribe it as soon as

possible onto old fashioned paper - or better

yet the archival quality kind. While this can

never duplicate the inflections and gestures

that accompany oral communication, it can

preserve a significant part of the information

in the event that technology changes too

quickly for reformatting. Printed transcripts

are also easier to use in locating specific

information since they can be quickly skimmed,

are ideally indexed, and digital files can be

text searched by computer. Realistically,

transcription is time consuming, tedious, and

creates additional challenges. A good

transcription includes everything from the most

awe inspiring sentence to bracketed editorial

notes identifying background noises such as the

ring of a rotary telephone. The WPA interviews

were written by artists. The literary flow of

many Life Histories is far from the realistic

false starts, pauses, and ums that make up real

conversation. The literary approach also can

add significant biases and interpretations by

the interviewer far from the original

conversation. The interview of Marson Baynard

demonstrates this tendency as A. T. Long's

rendition of the interview took on a more

fictional tone, casting the family into

specific roles that would be appealing and

entertaining to an audience. Long also used

pseudonyms for the individuals he interviewed.

This is a controversial but at times

appropriate way to publish interviews. When

used, somewhere there should be a record of who

is really who such as the real names and their

story equivalents presented in the current

online account of the Marson Baynard "Up Hominy

Creek," interview located on the Library of

Congress American Memory Web Page.

Beyond the problems of transcribing an

interview without adding poetic license,

interviewers must constantly be aware of how

their questions and comments and even gestures

are influencing the answers themselves. But

questions are very much necessary. Before

conducting an interview, it is helpful to

conduct some background research about a

specific topic to know the terminology and

processes as well as how the individual to be

interviewed is connected to the topic in order

to create guiding questions. Beginning with

basic questions such as name and birth date

helps everyone get used to the interview

situation. Having prepared more questions than

can possibly be covered provides direction when

usually long winded people suddenly have very

short answers, especially with a recorder

present. While questions help guide the

interviewee to cover desired topics, they can

also add an external version of history while

subtly pressuring the individual to validate

that information. The story of Marson Baynard

in the American Life Histories does not provide

information about what questions were asked.

After all, this would seriously distract from

the literary approach A. T. Long and other

interviewers were working to attain as writers

and artists. As a result, current researchers

do not know what questions prompted the Baynard

family answers and what influence these might

have had in eliciting desired but perhaps not

entirely accurate responses.

Ultimately oral history reaches beyond

technology and transcripts and interviewers -

it is about the people being interviewed. The

words of the individuals reflect the most

significant aspect of the interview, and the

most important part of considering how the

interview can be used in research. Here,

researchers need to consider how the individual

was connected to the events reported. If the

individual was not actually there but was told

about an event, then the interview has moved

from recording oral history to recording local

tradition. Both are useful as long as the

limitations are considered. The temptation to

quickly record memories of older individuals

can become problematic when the individual has

aged beyond the limits of reliable memory.

Also, think about how an individual's personal

connection to the events may influence the

reporting. When the character of Marson Baynard

reported church as an excellent place to sleep

this opinion probably was not shared by many if

not the majority of parishioners.

Finally, oral history has brought its share

of lawyers into the research process since A.

T. Long and other Federal Writers Project

interviewers spoke with individuals from all

walks of life in all parts of the country. The

latest copyright regulations ensure that

anytime words are placed into any kind of fixed

media - be it in ink or digital recording, they

are immediately protected by copyright. Before

publishing interviews in a book, posting them

on the Internet, or simply placing them in an

archive for public access, the person being

interviewed has to sign a copyright release.

This is an annoying but ethically and legally

necessary formality. Regularly individuals try

to donate interviews to archives but cannot

since these institutions have to play by the

lawyers rules. Legal and other such details can

take the fun out of interviews on an individual

level. Often, it is helpful to work with an

established oral history project that can

provide the legal forms, place for permanent

storage, and other technical support so that

the interview process itself can return to an

enjoyable experience. In Transylvania County,

the Transylvania County Joint Historic

Preservation Commission has an established

ongoing oral history project housed at their

archives in Brevard, North Carolina.

The evolving field of oral history has moved

stories and memories from the simplicity of a

warm spring front porch to the boxy dark

organization of a library archives. Something

gets lost in the act of preservation like the

reality that green beans never taste quite

right after having been frozen. But these

interviews have also become an important part

of historic research for twentieth - and

twenty-first - century topics. The important

thing is to remember the same rules as come

into play with any source. No single source or

even type of source should be the only part of

research. Ultimately, the researcher is

responsible for evaluating the reliability and

usefulness of a source in context of the

subject being studied. Source information

should be included so that future researchers

can find more information or possibly correct

information later on. These citations may be a

formal footnote with dates, names of the

interviewer and interviewee, and repository

with an accession number. Or it could simply be

a mention of a "personal conversation with"

that too often has to substitute when words are

spoken before the electronic stores and

archivists and attorneys can enter into the

seemingly simple act of documenting

history.

- Linda Hoxit Raxter -

originally posted April 29, 2003

^ Back

to Top ^ Back

to Top

|