![]()

![]()

North Carolina Algonquians

by Christian F. Feest

(1978)

Part 1

![]()

Language, Territory, and Enviornment

The Algonquian-speaking tribes who once lived in coastal North Carolina represent the southernmost extension of Algonquian groups along the Atlantic seaboard.* Like their Virginia relatives to the north they combined a southeastern habitat with a northeastern heritage and are grouped together with them as "southeastern Algonquians." Differences in cultural as well as natural environment brought about variations of the same basic pattern, which justify separate treatment.

* (The language of the North Carolina Algonquians is no longer spoken. In the absence of adequate early recordings, the spelling of native terms and proper names follows their historical orthography.)

To the north, the tribes of eastern North Carolina were bordered by Virginia Algonquian groups and by the Dismal Swamp. Unlike the situation in Virginia, there was no natural western boundary to Algonquian territory; and the coastal plain extending farther to the west and south of it was inhabited by Iroquoian tribes. It is in fact very hard to define this boundary clearly all along its course. The Tuscaroras, for example, were claiming all the region west of Chowan River and south of Cuttawhisikie Swamp during the seventeenth century; but in 1585 several villages, presumably or even certainly belonging to Algonquian tribes, had been located in this region (Hoffman 1967).

Evidence for the linguistic relationship of coastal groups with the Algonquian family of languages is small. Less than 100 words, besides place, tribal, and personal names, were recorded by the English colonists of the Roanoke voyages. In all likelihood these were mainly from the Roanoke, Croatoan, and Secotan dialects (Quinn 1955, 2). Another 37 words, this time of the Pamlico language, were published by Lawson (1709). Both word lists are sufficient to prove an Algonquian affiliation of those groups. Other tribes can be classed as Algonquians only on nonlinguistic grounds. The Weapemeoc and Chawanoke tribes may be considered as certainly belonging to this family. The evidence for the Moratuc (Mook 1943c) and Neusiok is far from convincing; both may have been Iroquoian tribes. Algonquian afffliation of the Pomouik rests on their suggested identity with the Pamlico.

The North Carolina coastal plain has an almost flat surface with many lakes, extensive swamps, and sand dunes. The coastline is deeply indented by sounds (Currituck, Albemarle, Pamlico) and tidal rivers. A chain of narrow islands and sand bars closes the sounds against the Atlantic Ocean. Predominately sandy soils are covered by coarse grasses, marsh vegetation, and evergreen forests. Climate is of the humid subtropical variety, with an annual growing season of about 250 days. Both freshwater and saltwater fish, oysters, and clams are abundant in the coastal region, which is also much frequented by local and migrant water birds and by game birds. Mammals include deer, fox, squirrel, opossum, rabbit, and in former days also bear and puma.

![]()

Archeology

Very little is known about the archeology of coastal North Carolina. On the basis of a survey made by Haag (1958), a few sites in this region may be tentatively identified with historic Indian villages. For the area occupied by the Roanoke and Croatoan Indians, shell-tempered pottery appears to be typical, which indicates similarities with tidewater Virginia. Clay-grit tempered wares predominate along the Chowan River; sand-tempered pottery characterizes the Secotan area. Thus, a greater differentiation of protohistoric manifestations than in coastal Virginia becomes apparent. Late cultural influences from the south can be traced in an increase of simple stamped sherds.

![]()

Late Sixteenth Century

The history of early European contacts along the North Carolina coast is similarly clouded. Several explorers, including Giovanni da Verrazano in 1524, are credited with reaching that region and even contacting the Indians; however, evidence is in no case conclusive. Native traditions recorded at the time of the English colony on Roanoke Island refer to only one previous contact with Whites: in 1558 shipwrecked people, probably Spanish, were saved by the people of Secotan and after a short time tried to make their way home on an improvised ship. Other ships wrecked on the Carolina coast first provided the Indians with iron implements (Barlowe 1589). For most Indian groups in coastal North Carolina, the history of European contacts therefore began only with the first arrival of the English ships in 1584 and the establishment of a colony one year later.

![]()

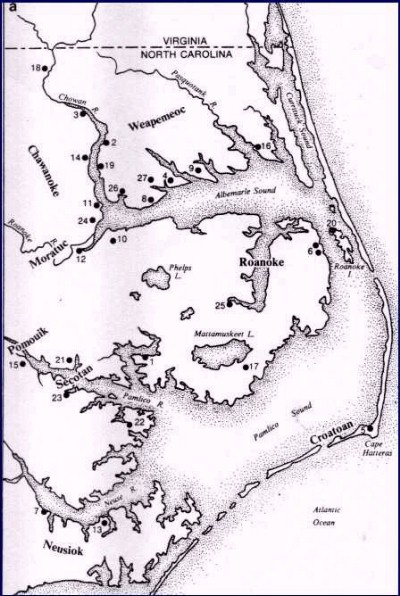

Figure 1a. Tribes and

villages 1585/6. 1. Aquascogoc; 2. Cautaking; 3. Chawanoke; 4. Chepanoc;

5. Croatoan;

6. Dasemunkapeuc; 7. Marasanico; 8. Mascomenge; 9. Masequetuc; 10. Mequopen;

11. Metacquem;

12. Moratuc; 13. Newasiwo; 14. Ohanoak; 15. Panauuaiok; 16. Pasquenoke;

17. Pomeiooc;

18. Ricahokene; 20. Roanoke; 21. Seco (Cotan); 22. Secotaoc; 23. Secoton;

24. Tandaquomuc; 25. Tramaskecooc; 26. Warawtan; 27. Weapemeoc.

![]()

Figure 1b. Tribes and

villages, 1657-1795. Some locations are tentative. Arrows mark tribal dislocations.

Dates in parenthesis indicate documented periods of occupation of villages.

1. Cape Hatteras Indian Town (1708-1788); 2. Chatooka (1708-1712); 3. Chowan

Indian Town (1707-1795);

4. Katoking (1657); 5. Mattamuskeet ((1733); 6. Pamlico (1708); 7. Paspatank

(1708);

8. Poteskeet (1708-1733); 9. Raudauquaquank (1708); 10. Rickahock (1657);

11. Rouconk (1708-1712); 12. Wohanoc (1657); 13. Yeopim (1696-1733).

![]()

Demography

Very little is known about late sixteenth-century demography. Figure 1a provides information on the distribution of tribes and villages reported by the sources. The total number of tribes and villages was probably somewhat greater than these. Thus, there is evidence that the largest tribe encountered by the English (possibly the Chawanoke) had 18 villages and a population of around 2,500. The total North Carolina Algonquian population must have been 7,000 or more by 1585. Estimates of individual tribal strengths made by modern authors are nothing but informed guesses (Mooney 1928; Mook 1944a); most of them appear much too low (Feest 1972). Density of population was certainly greater along the rivers than near the sounds or on the outer banks.

Tribal boundaries cannot be established beyond doubt. Allied but independent groups were sometimes regarded as single tribes by the European observers. Thus, the Roanoke, Croatoan, and Secotan tribes are frequently referred to as one tribe (Mook 1944a). Uncertainty about locations of villages makes assignments to tribes difficult. This applies particularly to the Weapemeoc, Chawanoke, and Moratuc, and to the Algonquian boundary with their Iroquoian neighbors. Early depopulation was mainly the result of imported European diseases. During the presence of the early English colonists in coastal North Carolina, measles, smallpox, and colds must have pushed the death rate to 25 percent or more in some villages (Hariot 1588). Losses suffered through warfare with the English were only slight, although intertribal warfare was held responsible for the fact that "the people are marvelously wasted, and in some places, the Countrey left desolate" (Barlowe 1589).

![]()

Interethnic Relations

Soon after the English established their colony on Roanoke Island in 1585, differences among Algonquian tribes in their relations with the Whites became apparent. The Roanoke Indians, who most clearly felt the presence of the English, became increasingly disenchanted with the colonists whom at first they believed to possess supernatural powers. On the other hand, a pro-English faction was formed by those Indians who hoped to profit from trade and alliance with the colonists. This in turn led to a weakening of old alliances between Indian groups: the Croatoans sided with the English against the Roanoke; part of the Weaperneoc followed the Chawanokes' advice to stay neutral; while the rest of that tribe joined the Roanokes. There is evidence for precontact hostilities between the Secotans and their allies, and the Neusioks and Pomouiks. The Chawanokes were generally on good terms with Virginia Algonquians as far away as the Kecoughtan, who at that time were not yet part of what later became Powhatan's state; but they--probably like most Algonquian groups of the region--were frequently at war with the Tuscaroras (Mangoaks) though the Roanokes believed they could count on the Tuscaroras in their fight against the English (Lane 1589; Barlowe 1589).

The final fate of the "lost colonists" of 1586 and 1587 remains unknown. The first group was driven by the Roanoke Indians from Roanoke Island, removed to a location near the Croatoan tribe, and disappeared before the 1587 supply arrived from England. Those left behind in 1587 apparently also first left Roanoke Island for Croatoan, but reports gathered by the Virginia colonists after 1607 suggest that they made their way to the west and/or north (Quinn 1955). What lasting effect their prolonged presence in coastal North Carolina may have had on the Indians can only be guessed.

Indian-English contacts took place mostly on a personal level and were in all probability limited to members of the Indian upper class. Reasons for contacts included trade, political maneuvering, search for geographical knowledge by the English, and exchange of information on the respective cultures, particularly on religion. These contacts were restricted in consequence of the small number of bilinguals on both sides, which included on the Indian side two Indians who had been taken back to England in 1584 (Quinn 1955).

![]()

Subsistence

Early English reports on native economy give no clues on the relative importance of hunting, gathering, fishing, and horticulture. It can only be assumed that fishing was of even greater importance here than among the coastal tribes of Virginia.

|

|

Corn cultivation (figure 2) was the basis for the sedentary life of the Indians. Three varieties of corn (among them, Northern Flint) were planted from late March to early July. After the fields had been cleared of weeds by both men and women with wooden hoes, holes about one yard distant from one another were made with digging sticks. Four grains of corn were put in each hole, which was then covered with earth. As in Virginia, no fertilizers were used. In separate, sometimes fenced patches or in the corn fields were planted two varieties of beans, at least two kinds of gourds and pumpkins, sunflowers, and chenopodium or amaranthus. Tobacco was always grown in separate fields. Harvesting of corn was done from July to September; long growing seasons allowed two crops to be harvested from the same field in one year, but this was not the rule (Hariot 1588, 1590; Hulton and Quinn 1964; Sturtevant 1965; Bland 1651; Smith 1624).

![]()

Source:

North Carolina Algonquians by Christian F. Feest, in "Handbook of

North American Indians" (1978), Vol. 15, 271–281; Bruce Trigger, Editor.

Smithsonian: Washington, DC.

![]()

Copyright ![]() 2001

2001

Carolina Algonkian Project

![]()