Return to Currituck Co.

![]()

Currituck County Photographs

![]()

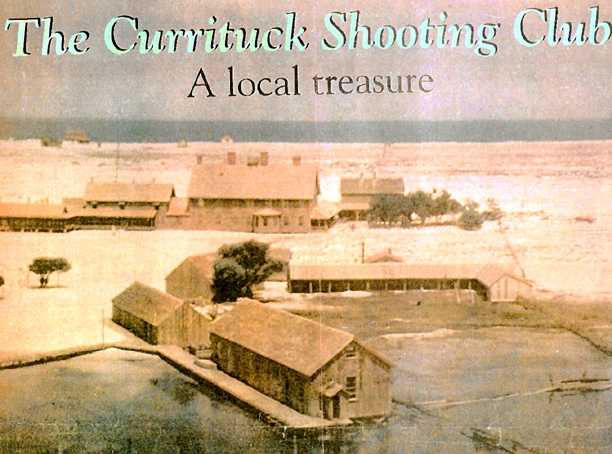

| Currituck Shooting Club |

The following article appeared in The Virginian Pilot on March 22, 2003. The 124-year-old cabin of the Currituck Shooting Club, the nation's oldest active club of its type, burned to rubble Thursday evening in a fire that was so hot and fast that firefighters were unable to get near the building when they arrived. Firefighters pulled in shortly after 5 p.m. to see flames blasting out windows and flashing across the roofline of the three-story building in Corolla. "It's an uphill battle when the fire is coming out the roof when you get there," said Corolla Fire and Rescue Chief Marshall Cherry. "We were limited in moving around the building because of the heat. It was hot enough we could drive around it but not walk near it." With no fire hydrants in the area, firefighters slogged to the shore of the Currituck Sound to pump water. Winds gusted 35 mph to 40 mph during a thunderstorm, and firefighters stayed at the scene through the night to protect nearby woods and homes. Investigators worked Friday to find the cause of the fire, which is believed to have started in the southwest corner of the building. The club's live-in caretaker and his family weren't in the building when the fire started, and nobody was injured. But the club and the caretaker's quarters were reduced to a smoldering pile. When Ann Colombell, a Connecticut resident visiting the area, drove past the club at about 4:50 p.m. on her way to a grocery store, she saw no signs of fire. Less than an hour later, she drove past the club again and saw it burning. "Within 40 minutes, the building went up and was gone," she said. "They had ammunition in there, and we could hear the powder or bullets exploding. It went down in a flash." The solid-wood building, assessed at $156,528, was uninsured, and club members have not yet decided whether to replace it. For now, most people are talking about what can never be replaced: historic documents and furniture, decoys and other artifacts that burned inside the building. The loss "is not dollars, it's history,'' said Calder Womble, one of 11 owners of the clubhouse and a longtime member. "Every room had old decoys, pictures we liked and some furniture that must have been there since the 19th century." The club began in the 1850s, when Northern businessmen met in New York to plan an exclusive group that would travel to Currituck County and hunt the area's plentiful flocks of geese and ducks. At the time, the area had a widespread reputation for being a hunter's paradise. In fact, the county was named after an Algonquian word meaning "The Land of the Wild Goose." Club members bought 3,100 acres in Currituck County for $1 an acre and built a cabin in 1857, according to the North Carolina State Historic Preservation Office. The first cabin was nearly destroyed during the Civil War, and members built a new clubhouse in 1879, according to records from the club's nomination form sent to the National Register of Historic Places. In 1980, the clubhouse was placed on the register. Membership in the club has always been highly exclusive, and nonmembers couldn't enter the clubhouse without an invitation from a member. Womble, a lawyer with Womble Carlyle Sandridge & Rice in Winston-Salem, joined the club in the 1960s because his friends were members. Once in, he had to pay a $3,000 yearly fee. Later, dues were raised to $5,000. By most accounts, the clubhouse was rustic, without many of the amenities the wealthy club members could afford. Until the 1960s, kerosene stoves heated the rooms, and bedrooms had chamber pots instead of indoor bathrooms, said John Wood, a restoration specialist with the state Historic Preservation Office. The outer walls were lined with weathered cedar shingles, and the interior had hardwood floors, plaster walls and hardwood pine ceilings. After various remodelings, club members kept one bedroom in its original condition and filled it with clothes, furniture and plumbing fixtures from the 19th century. The living room was never significantly changed and had much of the building's original furniture, said Carl Ross, superintendent of the Currituck Shooting Club from 1977 to 2001. When Ross retired, his brother, Alex, took over the job and moved into the keeper's quarters. "The clubhouse had an aura about it . . . 90 percent of the hunt was about the clubhouse," Carl Ross said. "Numerous famous people in the past sat in the same chairs. It was the same view they had in the 1800s." Barbara Snowden, a Currituck High School teacher and a local historian, said one of the major losses in the fire was the collection of logbooks and records that had been stored inside the building. None of the documents had been transferred to microfilm, she said. The documents recorded visits from famous Northern business tycoons and club members, such as J.P. Morgan and W.K. Vanderbilt, according to a display at the Currituck County Library donated by Mary Poyner Glines, daughter of one of the clubhouse's earliest superintendents. Hunting in the area rapidly declined in the 1990s, while houses and a golf course were built. Now, only about 13 acres of the clubhouse's property remains undeveloped, Ross said. "This property preserved a natural area in Currituck County, which is rare with all the development in the area," Wood said. "It was a rare example of a vanishing property type." A follow-up

article on the fire appeared in the same paper on April 5, 2003

|

![]()

Newspaper articles kindly submitted by Denny Denslow and Ben Bateman. No part of this document may be used for any commercial purposes. However, please feel free to copy any of this material for your own personal use and family research.