A homeowner's plan to rebuild a simple man's life

(The Virginian-Pilot - April 17, 2014 by Jeff

Hampton)

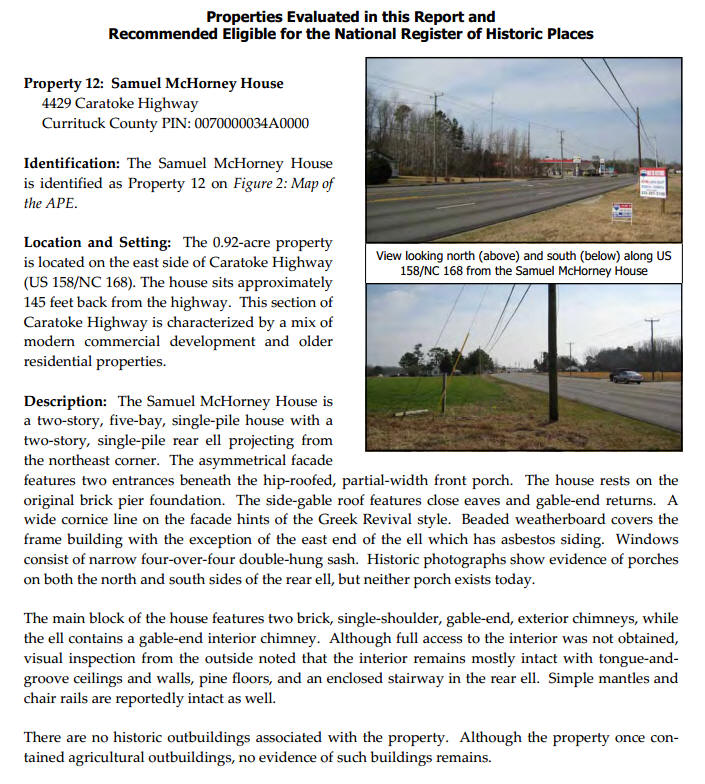

COINJOCK, N.C. - Erica Mason stood in the sunlit front room of a house

built when George Washington was president, awed by the simple lifestyle

of Edmund McHorney, the last person who lived there.

McHorney died in 1964, when even in rural Currituck County people watched

television, stored leftovers in refrigerators and took showers in indoor

bathrooms.

McHorney lived without such conveniences all of his 86 years. The

two-story home, built of hand-hewn timbers connected by wooden pegs, never

had electricity or plumbing.

Mason held up an aged chamber pot.

"This was Edmund's bathroom," she said. "He simply lived here. He's the

most simple man ever."

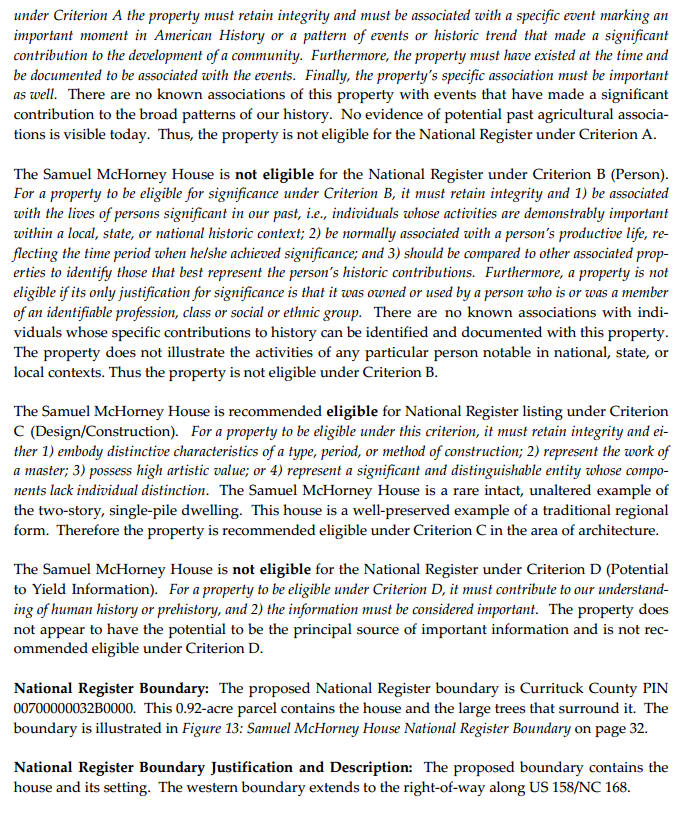

Mason bought the house, set prominently on 2 acres on U.S. 158, in June. She saved it from collapse or demolition with plans to restore it into a

museum of local farm lifestyle.

She said she could not bear seeing the old structure destroyed after

driving past it daily from her former job to her Coinjock home.

"This is an amazing house," she said. "After 200 years, it's still

standing."

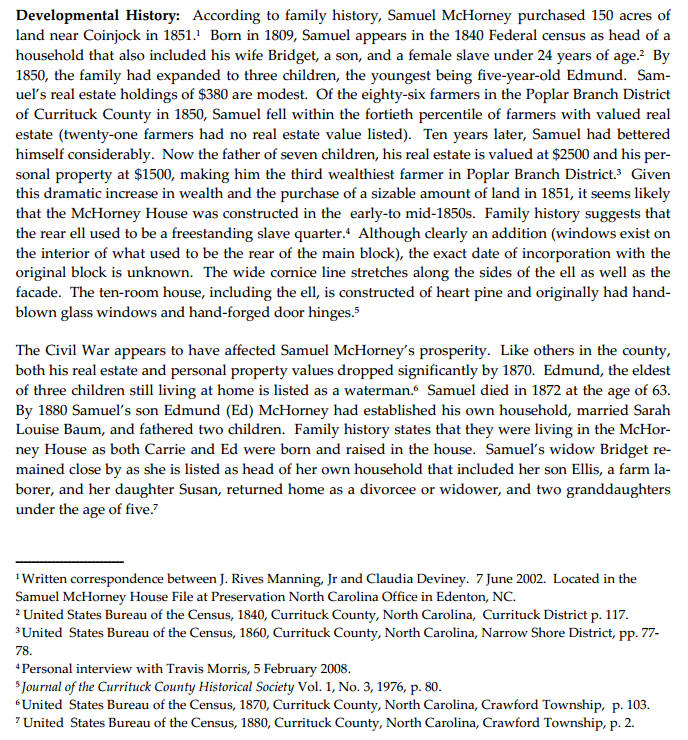

It is uncertain when the restoration will be finished. Mason hired Moyock

contractor Tim Fenton, who in December began replacing cypress siding,

shoring up original handmade brick piers, rebuilding the country porches

and jacking up the sagging back end, the hardest task of the renovation.

"We started from the ground up on this one," Fenton said.

One of Currituck County's earliest families, the Simmonses, built the home

in 1790 from rot-resistant juniper timbers cut from nearby woods,

according to Mason's research. Someone used a finger to inscribe the year

"1812" in one of the bricks of the chimney that was added later.

The back half of the house was salvaged from a burned home on the property

and added just before the Civil War. Termites and carpenter bees had

ravaged the less hardy pine boards of the addition.

Fenton commissioned sawmills from the region to cut timbers large enough

to match originals. One surviving hand-hewn piece across the front is a

board 5 inches thick by 8 inches wide and 32 feet long.

Carpenters saved old windows and matched newly made sashes for the wavy

blown-glass panes. Hair from horses on the farm reinforced the old lime

and sand interior plaster. The ax marks of Colonial craftsmen are visible

on the rafters and beams.

"There is nothing in this house the same size," Mason said. "This has made

me so thankful for carpet, thankful for a sink."

The single mother of a grown daughter would say only that the renovations

cost more than expected. It is restored to the standards required by

Preservation North Carolina, a nonprofit.

Mason plans to add modern bathrooms, built in back like outhouses. A

discreet lighting system will mimic techniques used at Jamestown, she

said.

McHorney never married, never had children. He was born in the house and

remained there all his life. His parents died when he was a young man. He

farmed for a living, mostly raising watermelons and selling them at what

was once a bustling canal waterfront here.

McHorney occasionally took the watermelon boat north and spent time on

Baltimore's Light Street, said his great-nephew Travis Morris, who lives

nearby and remembers "Uncle Ed."

In his later years, McHorney drove his 1931 Pontiac daily down U.S. 158 to

the store and post office near the Coinjock Canal, a part of the

Intracoastal Waterway. It was the only car he ever owned.

He heated and cooked with coal and firewood. His vintage icebox remains at

the house, the ice bucket and tongs still sitting on top. He typically

cooked his own breakfast and ate lunch at his sister's house next door.

McHorney never bothered to replace the roll-up window shades installed in

the 1890s.

He was known to be cantankerous. He kept a pistol under his goose feather

pillow, Morris said.

McHorney once borrowed a mule from his brother-in-law. When the

brother-in-law wanted to borrow McHorney's mule later, McHorney wouldn't

let him, Morris said. The brothers-in-law didn't speak after that.

And once while driving home in his Pontiac, he tried to turn into his

driveway without signaling. A New Yorker passing through struck McHorney's

car without injuring him. McHorney scolded the visitor as if the accident

were his fault, Morris said.

" 'My God, man, don't you know I live here?' " Morris said, quoting his

great-uncle.

The New York man was perplexed, but more people will soon know Edmund

McHorney lived there - simply.

|

|

| The front porch of a house in

Coinjock. N.C. that dates to 1790 and is being restored thanks to

grant money. The home's owner, Erica Mason, plans to open the

home to the public as an "odditorium" which will feature odd items

from the home's time period.

Photo taken Wednesday, April 16, 2014 by Brian J. Clark for The

Virginian-Pilot. |

|

|

| Contractors and restoration

specialists Tim Fenton (left) and Rick Smith plane floor boards for a

home near Coinjock, N.C. on Wednesday, April 16, 2014. The home

is being restored through grant money available to rehabilitate

historic buildings.

Brian J. Clark for The Virginian-Pilot. |

|

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()